Ryan HockensmithOct 30, 2025, 08:30 AM ET

- Ryan Hockensmith is a Penn State graduate who joined ESPN in 2001. He is a survivor of bacterial meningitis, which caused him to have multiple amputation surgeries on his feet. He is a proud advocate for those with disabilities and addiction issues. He covers everything from the NFL and UFC to pizza-chucking and analysis of Tom Cruise's running ability.

THE FIGHT BEGINS with space. Marcus Kowal takes two steps back to the edge of the jiu-jitsu mat, and then one step toward his opponent. It's the jiu-jitsu equivalent of throat-clearing before a big speech -- and this is a big speech for him.

Kowal is a 48-year-old brown belt who hasn't competed in six years. But now, in late May, he is participating in a massive jiu-jitsu tournament in Long Beach, California, with the hope that winning his weight class could help him finally get bumped up to black belt. But more than anything, he hopes people will read his gi and help join what he calls the biggest fight of his life -- the fight to change America's drunken driving laws.

Before the bout, Kowal (pronounced Koe-vaul) had jitters. It's not that he is scared to compete, or get hurt, or lose in front of his three kids. It's what he is wearing on his back, literally. His gi is covered in remembrances of his first child, Liam.

On Sept. 3, 2016, Liam Kowal was in his stroller for a walk when a drunken driver struck him and his aunt, Allison Bell, on a crosswalk in Hawthorne, California. Bell survived, but Liam was killed. Kowal and his wife, Mishel, correct anybody who asks about their three kids. "We have four children," Mishel says. "With Liam." They are with Liam, always, even if he is no longer with us.

He is with Liam at this very moment, as he strides back toward the center of the mat. His opponent, another 40-ish brown belt named Jeff Mora, eats up the space in between and suddenly they are engaged, grabbing for legs. Mora gets him down and mushes Kowal's face for several minutes as Kowal uses his hands to frantically create some breathing room.

This kind of predicament is no big deal for Kowal. He has been fighting since he was a little boy fistfighting classmates in Sweden, up through his time in the Swedish Special Forces, into kickboxing (black belt), Krav Maga (second-degree black belt), jiu-jitsu (high-level brown belt) and a 5-1-1 record as a pro MMA fighter. He is modest, both in size (5-foot-7, 154 pounds) and demeanor. But he walks upright, chin held high, like a man who could leg-kick the hell out of you. He isn't panicking.

Suddenly, Kowal explodes and ends up on top as his cornerman, friend and training partner Jair "Sinistro" Lacerda, yells, "Heavy! Stay heavy!" Kowal sees an opportunity for a finish, rolling Mora to his belly as he locks in a choke from behind. At the 4:35 mark, Mora taps the mat.

Kowal slowly rises to his feet to get his hand raised, but he can barely move. He's folded over, his head at his knees, exhausted. Sinistro, which means Sinister in Portuguese, won't let him stay there, though. He is a 40-year-old black belt covered in tattoos who smiles and jokes nonstop, but the Sinister of him seems like it's always available for summoning. He looks at Kowal, who is technically his boss at Kowal's gym, and motions for him to stand and be victorious. Kowal complies and gets his hand raised.

Twenty feet away, his kids Luna, age 6, and Nico, 7, jump up and down to celebrate, as Mishel records the entire match with her cell phone. Their youngest, 6-month-old Milo, is flailing around in a BabyBjörn carrier across Mishel's chest. Kowal acknowledges them with a big smile, and he points to the smiling green frog logo on his gi that reminds everybody that somewhere Liam is jumping up and down, too.

LIAM'S NICKNAME WAS "Beibisen," which is the Swedish word for "the baby." He had a big forehead and a bigger smile. He loved people, so his second home was his dad's gym, Systems Training Center, in Hawthorne, where he could roll around with his parents and other martial arts kids.

The accident happened when Liam was only 15 months old. The driver, Donna Higgins, pleaded guilty to vehicular manslaughter and was sentenced to six years in prison. In his book "Life Is a Moment," Kowal has a photo of the tattered, flattened stroller, which he often thinks about in his crusade to rethink American DUI laws.

America has some of the most lenient drunken driving laws in the world. The legal blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is .08 in every state besides Utah, where the limit sits at .05. In more than 100 countries worldwide, the legal limit is .05 or below, with some as low as .02. That's the level when impairment begins to affect drivers, and visual functions and multitasking begin to decline, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The agency says drivers with a BAC of .08 are four times more likely to crash than sober drivers.

In 1982, about 25,000 people died in drunken driving accidents -- a number that declined over the next three decades thanks to a massive public push against drunk driving, led by MADD. In the 2010s, that number stabilized, hovering close to 10,000 deaths, until an unexpected spike in 2021 when alcohol-related traffic deaths reached 13,384.

Even with slight drops in 2022 and 2023, Kowal and other activists believe this is a critical moment to curb drunken driving. They point to data showing that 30% of all traffic fatalities in the U.S. involve drunk drivers, and among those deaths, 40% are non-driver victims, including pedestrians and passengers.

"This is a crisis, and it's getting worse," Kowal says.

Kowal believes now is the right time to start a wave of versions of Liam's Law, named after his son and first introduced in California. Liam's Law would lower BAC requirements to .05, and Kowal has been taking every speaking opportunity he can across the country at Rotary Clubs, with state legislatures, AAA, ride-hailing app companies and just about anybody else who will have him. His broader goal is to raise awareness and generate social momentum that could ultimately lead to legal changes, and it's working, slowly. There are bills pending in several states, including Connecticut, North Carolina and New York, that would implement the .05 BAC.

"Progress has been made over the years, but we still have an enormous amount of deaths, and those deaths are preventable," says Dr. Steven Teutsch, an advisory board member of Kowal's foundation and a senior fellow at USC, who's spent decades researching ways to reduce alcohol-related traffic deaths.

Teutsch chaired an expert panel in 2018 for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine that investigated alcohol-related accidents and proposed potential solutions to reverse the trend. The panel suggested raising taxes on alcohol, decreasing the number of establishments licensed to sell booze, boosting education for alcohol servers and beefing up counseling services for people arrested for DUI.

But many of those proposals run into the same bipartisan quicksand that Kowal says he has encountered. Kowal has spoken to residents and lawmakers across the aisle and has been disappointed by the amount of people who nod along in agreement but ultimately do not feel compelled to do the work it would take to create such massive change.

Kowal says left-leaning and libertarian types he's encountered don't love the idea of more policing, which could lead to more racial profiling, more arrests and more judicial gridlock. The American Civil Liberties Union, for one, has publicly voiced these concerns around lowering the BAC. Right-leaning politicians, he says, tend to bristle at raising taxes and putting more regulations on businesses. "They agree with the idea," Kowal says. "But they want the work to be done for them."

That's part of the reason why Kowal is laser-focused on what he believes would be the most significant, doable change that the academies' report suggested: lowering the BAC from .08 to .05 in all 50 states, along with Washington, D.C. Kowal supports the consensus expert opinion that dropping BAC levels would have the biggest effect on lowering alcohol-related traffic fatalities. He was told that the driver in Liam's accident had a .12 BAC on her breath test.

Every state already has BAC laws, so legislatures would need to tweak existing laws, versus passing new ones. In 2019, lawmakers proposed Liam's Law to the California legislature, but it didn't make it to a vote because of a lack of support. That same year, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) endorsed lowering the BAC to .05. For years, the nonprofit had been a holdout, with founder Candy Lightner (who left the organization in 1985) saying that lowering BAC to .05 was "a waste of time." Her view was that most drivers between .05 and .08 could pass field sobriety tests, which would make prosecutors reluctant to try drivers in front of juries who might be unwilling to convict at that level of intoxication. After decades of remaining neutral, MADD finally changed course.

That makes Utah the ultimate place of hope for Kowal and his supporters. That state had been the first to go from .10 to .08 in 1983, fueled by an electorate composed of about 40% Church of Jesus Christ Latter-day Saints members who largely abstain from alcohol use. Utah's decision later played a part in the Clinton Administration advocating for other states to follow suit. By 2004, with a thinly veiled threat to withhold federal infrastructure funds, every state had gone to .08.

Then, in the late 2010s, Utah lawmakers began exploring dropping that number to .05. The state became a battleground between the American Beverage Institute, a powerful D.C.-based lobbying firm for the restaurant and hotel industry on alcohol-related issues, and anti-drunken-driving advocates like Kowal. His main job then -- and now -- has been to tell his story and advocate with legislators.

Kowal also wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post making the case for Liam's Law, and the lobbying firm responded with its own piece in The Orange County Register. "Lowering the legal limit does nothing to address the group of high-BAC and repeat drunken drivers who are responsible for the overwhelming majority of alcohol-related fatalities," the firm said, citing numbers that show the majority of fatal crashes involve people with a BAC of .10 or higher. The group also sponsored newspaper ads in Utah, Idaho and Nevada that said, "Utah: Come for vacation, leave on probation."

But Kowal & Co. won that fight, and a version of Liam's Law was implemented in Utah at the end of 2018. The following year, Teutsch says alcohol-related fatalities dropped about 19.89%. He believes there would be a similar result across other states if they enact similar laws. In a Hollywood-ized telling, this is the part of the movie where there'd be a giant celebration, and the camera zooms in on Kowal's face as he tears up, but that's not how Kowal operates.

Kowal is kind, funny and forgiving. Easy with a smile. But his soul is stoic. He celebrates by prepping for his next match -- and fighting for Liam's memory. He thinks his personal message will influence the rest of the country.

Kowal wants to restart conversations with California lawmakers in the near future, and he's still meeting routinely with AAA and ride-hailing apps to gather consensus. He finds soft support, but the workload always falls on him and Mishel -- all those polite head nods haven't amounted to as much action as Kowal would like. He knows this is going to be a slow, state-by-state, senator's-office-by-senator's-office march for years. Maybe for the rest of his life. And he will do it.

This is how Kowal processes his pain. He is a former military guy who got into MMA, where fighters are still bleeding from the win they just had when they start calling out their next opponent. Kowal did some therapy with Mishel after Liam's death, but sitting with grief feels like sitting still with his grief. He has to find the next fight and win, and then the next one after that. Even when he talks about the drunken driver who killed Liam, he has almost no edge in his voice.

"Justice was served," he says. "I thought it was light for the crime she committed, and her apology in court felt like she was saving her ass more than being actually apologetic."

And that's it. He doesn't come back to it. His words just linger in the air as he drives to the jiu-jitsu tournament. He drives forward because he can't look back, only forward. Sometimes that can be a pyramid scheme of processing. But Kowal finds celebration in the battle ahead.

After a full minute of silence, Kowal starts talking again, and it's a perfect window into how he must use his pain as a propellant.

"Someone asked me, 'Do you really think you can do this?'" he says. "And I said, 'Don't we have to try? Don't we have to die trying? Sometimes we have to sow seeds for trees we won't sit in the shade of.'"

KOWAL IS LOST. His head is going side to side as he tries to figure out whether he just missed his exit. He did. He listens intently as Google Maps tells him to make a U-turn. Once he's back on the road again, going in the right direction, he remembers one other thing he wanted to say.

"It's not .00 that we are arguing for," Kowal says. "I have no issue with people drinking. Go out. Have fun. Just be safe on the way home. Make a plan."

He's getting close to the arena, and Kowal starts to get amped up to compete. On the way to the tournament, Sinistro shows up with Kowal's gi. He'd had it made for Kowal and tells him to unfold it in the driver's seat before they pull out. Kowal holds it up in the air and looks at the logos for the website of his 501(c)(3), Liam's Life Foundation. "Perfect. It's perfect," he says.

Before his first match with Mora, Kowal walks the floor of the arena amidst a crowd of about 500 competitors and coaches. This is the most unassuming collection of arm-breakers and leg-lockers imaginable, many of them accountants, teachers and attorneys, and quite a few stop to hug Kowal. He's an A-lister in the California martial arts scene, even though his fighting career only got as high as Strikeforce in the U.S.

He wins the first match and has a whole five minutes to recuperate before the second one. They'll go best-of-three, so Kowal really needs to win the next one or else his energy levels could be problematic. Mora looks much fresher a few feet away.

The five minutes go by fast, and Kowal takes a big, worrisome inhale as he goes back on the mat. His lungs feel like somebody reached into his chest and has been pinching them, and the stakes of this day are complicated. On one hand, performing well in competition helps him as he closes in on being awarded his black belt in jiu-jitsu, which has been a longtime goal of his. On the other hand, he won his first match against a strong opponent and looked like he belonged, all while repping Liam in a way that he can always be proud of. If he truly has nothing left physically, he'll still feel some level of spiritual fulfillment at having competed and won once.

But Kowal's size and demeanor mask a man who is capable of incredible violence and competitive spirit. He is a fighting lifer, somebody who can roll out of bed throwing elbows and cranking necks. His life is fighting, and fighting is his life. When Kowal and Mora begin their second match, the lung-pinching recedes and the martial artist returns. He takes a step back and then surges forward, same as he will in all his bouts on this day. He looks like a different guy than he did 30 seconds ago. He gets in on Mora's legs and gets him down, then starts racking up points. The score is 2-0, then 6-0, then 9-0, and finally 16-0.

Throughout the whole match, his two older kids, Nico and Luna, hang on the side of the rail, cheering for him while Mishel tries to record on her phone with Milo still strapped to her chest. It's a losing battle. Milo, who was nine months old, has the athleticism and relentlessness that only a third-youngest kid in a house could have. Nico and Luna constantly carry him around, roll him on the ground, and cram into the stroller with him, so he is battle-tested before he can even walk. "They definitely do some loving on him," Mishel says.

When Kowal gets his hand raised in the second match, he is again doubled over and his lungs have been blowtorched. He is the Jiu-Jitsu World League "The Worlds" 154-pound gi adults Masters division gold medalist. His hair is frizzled, and he's coughing more than he's not. But 20 minutes later, he composes himself enough to stand on top of the awards podium to get his first-place medal.

He steps down and moves through the crowd to get to his family. He hugs his wife and Milo, who is now asleep. Kowal stands beside Nico and Luna, and they both reach across his hips to give him side hugs. They both have the confidence and attitude of two elementary schoolers who have been doing martial arts since before they could walk.

When they let go, there are a few seconds where Kowal just stares off into the distance. He has left some space for Liam to have a hug, too.

Later that afternoon, he competes in the no-gi division, and he runs into a bunch of hammers. Kowal goes 1-2 to finish fourth amongst a bracket full of sharks. When he winds his way out of the competition area, Mishel and the kids are waiting for him. It has been a long day for all of them, and Kowal looks both exhausted and ecstatic. He does a 1-2 combination kiss, first Mishel on the lips and then down to Milo's sleeping head. Luca and Nico both sidle up beside him and hug him around each leg, and it feels like the first time all day that Kowal doesn't go looking for any space.

THERE IS A PHYSICS concept called quantum entanglement, the idea that when intertwined particles split apart, even with a million miles between them, they remain connected on some level. And in that existential way, Liam will always be right beside his family, especially this morning. The day after the jiu-jitsu tournament, all five Kowals come down early and start setting up for a birthday party. Liam would have been 10 years old today, May 25, 2025.

The Kowals own a house not far from their gym, but a few years ago, with their lives swirling around running the facility, they began offering their home for short-term rentals, and they moved into the second floor of the Systems Training Center. So, it's Take Our Daughters and Sons to Work Day every day for Nico, Luna and Milo.

Mishel manages the gym, and also Marcus. She's the brains of the operation, and he is the brawn. They fell for each other at the same time 15 years ago. Marcus was a trainer at a local gym, and Mishel booked appointments. She wanted him to ask her out and didn't want to make the first move. He liked her, but he was -- and is -- a scurrying person. There's always a to-do list dancing in his brain, but asking out his coworker was always stuck on the honorable mention side of his list.

But even then, Mishel knew exactly how to read him and give the perfect nudge. She got his cell phone number and texted him about a possible client. Sure enough, this led to a date request from Kowal, and they've been together ever since.

They've shared so many missions since they met. She has helped him turn Systems into a successful gym in a crowded SoCal workout world, and they're incredibly doting parents. When they talk about their kids, they know them. Not just birthdays and favorite foods. They know what makes them happy and sad and scared and reluctant and angry and everything else.

And yet, the loss of Liam still impacts them, their relationship, their kids. Mishel was crushed when he died and couldn't get out of bed for days. She joined a group for parents who'd lost a child and began therapy, convincing a reluctant Marcus to go, too. Marcus wept and mourned Liam, but he must always plot a path directly through his sadness as soon as possible. By the time the funeral was held, Marcus already had documents for Mishel to sign to launch their Liam's Law Foundation and website. For her, it felt a little too soon. For him, the fight couldn't start soon enough.

It has been over nine years since Liam died, and they both still have open wounds, just in different ways. Mishel thinks about what Liam would be like, whether he'd do jiu-jitsu with Luna and Nico, and if he'd cram in the stroller with Milo, too. Marcus dreams of channeling Liam into a legacy, one Rotary Club and transportation board meeting at a time.

They also have slightly different visions for the foundation's future, and each explains the coping methods of the person behind it. Marcus sees a tactical march, one task after another, until every state has rewritten its DUI laws. He needs to know that there is something tangible that he can do.

Mishel imagines something that doesn't require them to relive their pain over and over again. Maybe that means the foundation has the money to build a bigger staff of experts who know how to work the legislative system. Maybe that means support groups for people who have lost a child. "Maybe it's all of the above," she says.

They will grieve together in the same way on this day, though. They've set aside the back room of the gym for a 10 a.m. celebration of Liam's life. It will be five, five-minute rounds of a surprisingly difficult workout that the Kowals lead every year to remember him. Mishel even picked up a big gold "10" balloon along with some of Liam's favorite treats: donuts. "The calories don't count today," Marcus jokes.

About 25 people do the workout. There are friends and family, plus a few members of the gym. Sinistro is there, smiling and playing with the kids. He cares deeply about Kowal in a way that goes beyond practice partners. "Marcus is great," he says. "Great as a martial artist. Better as a man."

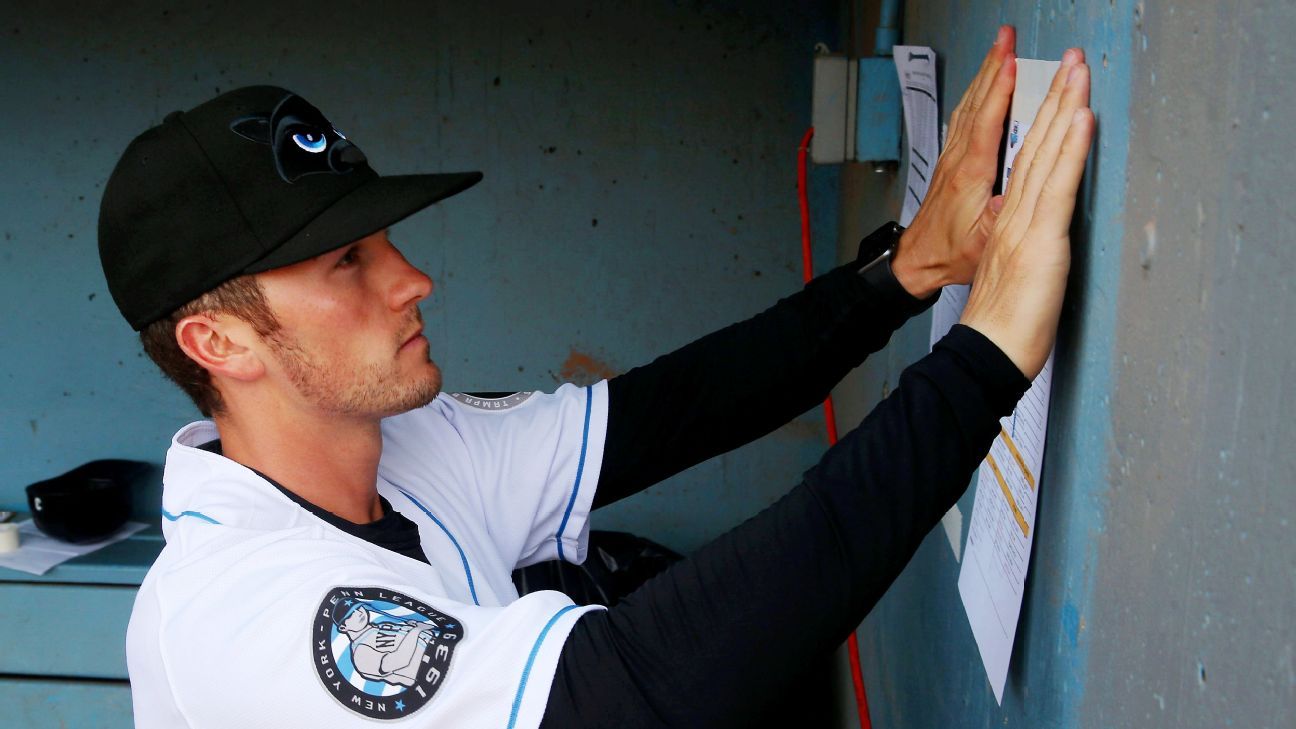

A little before 10 a.m., Kowal goes to a dry-erase board and starts writing out the workout. Both parents have specific things that help them remember their son. Marcus has set up the workout as five rounds and 25 total minutes to represent Liam's birthday.

By 10:10 a.m., the room has filled in nicely. Kowal spends a few minutes trying to explain the workout with words. But people seem confused. Nico and Luna are bouncing around, ready to do arm hangs, upside-down pushups and dead lifts along with the adults. Milo wants to do everything, too, but he is trapped in a playpen, which he is loudly objecting to with a squeaky yelp that resounds through the gym. All three kids have on clothing with green frogs on their outfits, which is in honor of Liam's favorite stuffed animal, a green frog.

Kowal keeps explaining the workout as he points to the dry-erase board and then to the equipment. Yet, the glances and shoulder shrugs indicate that this isn't quite landing with attendants.

Mishel steps in without a word and starts doing each exercise as Marcus redescribes it. Marcus notices her and begins to incorporate her into the demonstration. They have an easy chemistry that doesn't always require words. It's the kind of nonverbal love language that only people who've been through some things together could ever have. Their quantum entanglement is deep.

When Kowal fires up some music and hits the timer to start the workout, people seem to have a better grasp of what they're supposed to do. The final bell rings 25 minutes later and everybody claps. Marcus and Mishel go to the front of the room to address the crowd. "Thank you for doing this," he says. "It means a lot to us. It's a hard day for us. Ten is a special number. The work that we do is important. We're trying to save lives. This was a pretty hard workout. But it represents sacrifice."

He looks toward Mishel to throw it to her and she says, "Yeah," and then she can't continue. She starts to cry and seems to hold Milo a little closer to her chest. Kowal jumps back in and encourages everybody to have a donut or three, and the kids all pounce.

The kids stand a few feet away from their heartbroken parents and a birthday balloon for their big brother, and a picture comes into focus. The fight of Marcus Kowal's life isn't just Marcus Kowal's fight. These are the five Kowals, ready for battle for the next 100 years, all for Liam.

Luna and Nico are halfway through their glazed donuts when Milo goes back into the playpen. This bums him out enormously and he won't stop chirping in the direction of Luna and Nico. He goes to the side of the playpen and pushes his right hand onto the mesh barrier holding him in there. Nico comes over first and high-fives him, which makes Milo smile.

But then Nico runs off toward his friends, and Milo is again sad at the distance between him and his siblings. Luna notices and comes over. Milo has his hand jutting out on the mesh of the playpen, and she reaches down with her right hand and they touch, palm to palm.

She begins to pull her hand back to run away. But she sees that Milo has leaned into the netting and planted his lips on the side of the playpen. She stoops down and tries to kiss him. But the angle is awkward and she has to keep turning her head more and more and more. By the time she's able to put her lips to the side of the playpen, she is sideways, parallel to the ground, completely mashed into the mesh. So is Milo.

They both start to fall to the ground, but the netting saves them. It creates the ideal amount of space between them -- enough to keep them from locking hands and dragging each other down, but so little space that their body weights prop them up as they press together. That allows them to gently glide to the ground, where they both look at each other and laugh. Luna runs back to her friends and Milo picks up a toy in his playpen, and they seem grateful to have been entangled in the most perfect way.